no more cultural cringe: in defence of australian rock

a sense of living in australia: pub rock vs punk

A quick note: Sorry for my absence. I’ve been exploring new avenues and such. Thought I’d publish my essay from my Australia Popular Music course because I absolutely killed it…………….. sometimes I feel like a fraud but a killer mark on an academic essay can save me.

A quick update: I’ve been running a weekly Oz/Pub rock show on SURG FM with my friend Aidan. Check out our IG here. I do play the part of content bitch. I quit my job as a music PR assistant! For Reasons. I’ve been running the SURG blog and editing posts. And, I started writing for HEAVY Mag! A total DREAM. That one is a story in itself though. Check out my first article here.

Australian homeland music has been characteristically soundtracking its country since its very inception, with this no less true for its pub rock and punk variants. Multiplicities excavated in what initially appears as stagnant gendered and immigrant identities provide a sense of diverse shades of living in Australia, whose emphasis on differing connections to land and place in narrative verse and illustrative sonics attempts to bring closer country and countrymen.[1] As categorically expected with punk and post-punk incentives, an evidently political veneer is adopted and strengthened in frequent protest songs. Although often less common, more covertly or even retrospectively, pub rock has its share of expressing vitriolic ethical stances that echo a sense of a fraught Australian political landscape and the voice of an impassioned population.[2] With distinctions in how bands visually or audibly express Australian life, both pub rock and punk make meaningful contributions to the country’s musical zeitgeist.

“Music videos, popular in the advent of the 80s due to the reigning distribution of music television, flip from footage of the band on dry dirt tracks and in abandoned shacks to beach-side scenery, reinforcing two iconic images of country: the coastal and the bushland.”

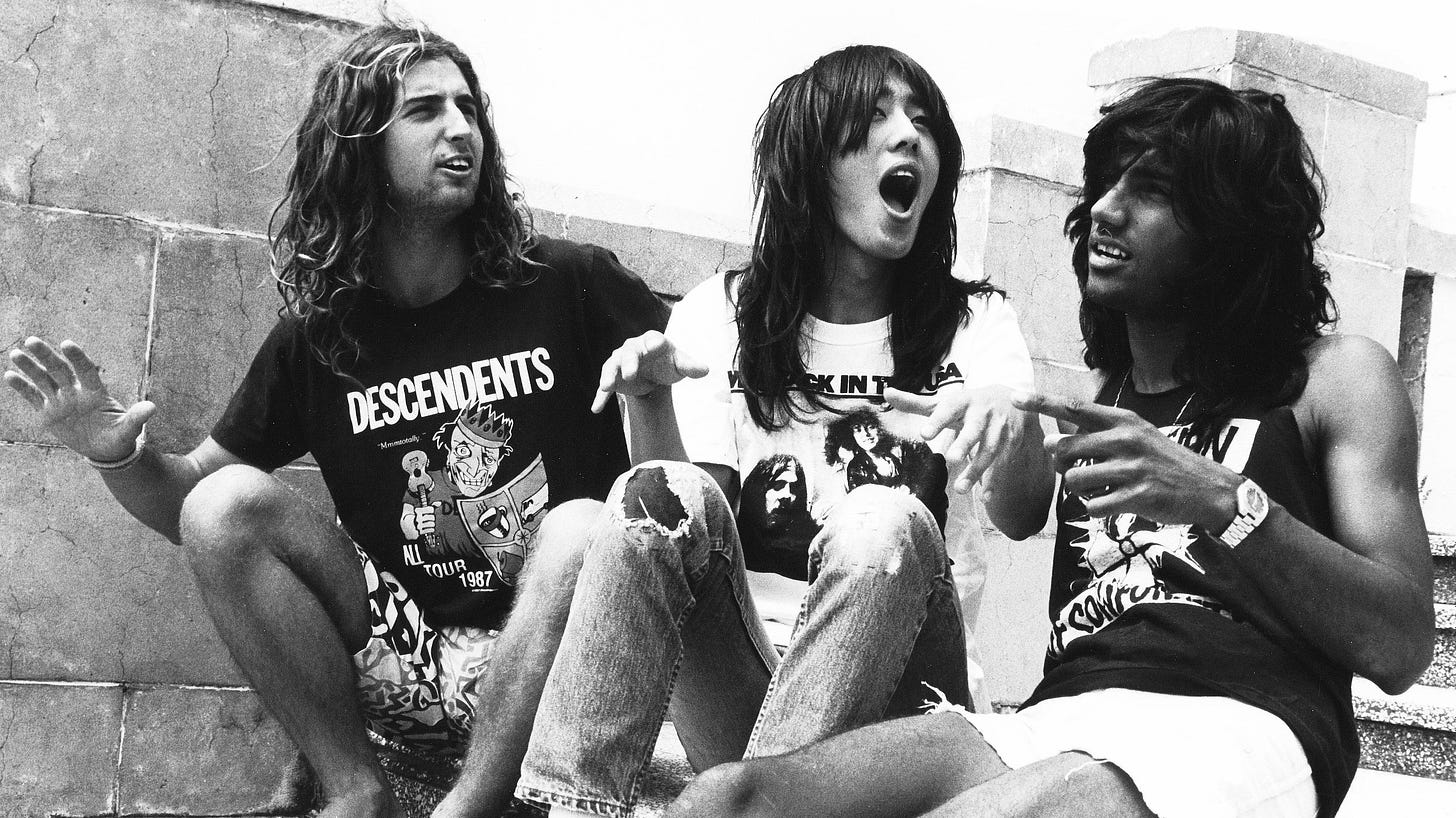

The Australian identity has long been established and developed in music in a way that usually attests a pride in citizenship. Its roots are found in the larrikin “Anzac Legend” which sets out a popular cultural memory of the white Australian male as “a bit of a boozer, a gambler, [having] a ruling creed of mateship” and with “respect for talent rather than status”. This easy-going, honest-working everyman features widely across the pub rock discography in the genre’s characteristic narrational tendencies.[3] While songs like The Choirboys’ “Boys Will Be Boys” have punchy, chugging guitar and a blues-influenced strong hard rock beat that sonically personifies masculinity[4], Jimmy Barnes’ hit “Working Class Man” lyrically confirms and further constructs a persisting form of the Anzac Legend and the concept of “normative Australian masculinity”.[5] The second verse explicitly paints a Western-cultured Christian (“He believes in God and Elvis”), who makes downtime for his mates (“He gets out when he can”), and has patriotically served his country (“He did his time in Vietnam”).[6] Similarly, popular female-fronted pub acts such as the Divinyls were also externally mediated as having an adjacent gendered identity, “exploit[ing] a typically masculine set of codes to perform a novel subject of music” which, although limited, was often outwardly feminised with an “assertive and confident sexuality”.[7] As these musical protagonists are a common trope in pub rock, it is more usual that the Australian identity diversifies in punk narratives. South-Western Sydney punk band The Hard-Ons were composed of immigrants of Croatian, Korean and Sri Lankan heritage, and although a lot of early punk bands were also Anglo immigrants like AC/DC and Cold Chisel, the multiculturalism of The Hard-Ons left them subject to racist attacks. The punk genre opened the sonic gateway for the band to retaliate by “play[ing] as hard as [they] can”[8] and further affirm their identity as diverse Australians lyrically in early tracks like “Coffs Harbour Blues”[9] and “Stairway to Punchbowl”, the latter being their predominantly immigrant hometown.[10] With pub rock strengthening traditional concepts of the Australian men and somewhat rigidly evolving for the female identity, the roguish elements of punk expand the Australian canon and strengthen distinct identities that serve an expansive sense of living in the country.

From the beginning, land has always played a large role in Indigenous music and it remains no surprise that emphasis on place is similarly adopted by following genres to provide select images of Australian living to their audience. In the case of pub rock, Young observes “men as solo performers or as part of a band have generally preferred to sing to the desert, ocean or sky rather than to an audience of adoring fans”, choices in location that reinforce previous assertions about identity such as the “nineteenth century bush legend and the institution of mateship” and their resulting “rigid aesthetic of masculinity”.[11] Music videos, popular in the advent of the 80s due to the reigning distribution of music television, like Australian Crawl’s “Daughters Of The Northern Coast” flip from footage of the band on dry dirt tracks and in abandoned shacks to beach-side scenery, reinforcing two iconic images of country: the coastal and the bushland.[12] Contrary to this and yet still in the mainstream, AC/DC’s “It’s a Long Way to the Top” offers an alternative metropolitan backdrop to their music, recording a live performance on the back of a flatbed truck on busy Swanston Street in Melbourne for music program Countdown.[13] Similar is true for the development of “mythologies of place” in the pub with its emphasis a display of “value of the pub circuit” which originally uplifts Australian rock bands.[14] Although traditionally associated with its namesake pub rock, the revival of Australian punk is making a trend of honouring the pub lyrically and visually. Amyl and the Sniffers’ hit “Security” details a night of drunken disorder and stubborn venue security[15], while both the up-and-coming Chats and the revived choppy punk of the Cosmic Psychos eulogise local hotel meals in “Pub Feed”[16] and “Nice Day to Go to the Pub” respectively.[17] Once again wrapped up in semi-mythical identities of boozing bushmen, both pub and punk rock paint vivid snapshots of the natural Australian landscape and the metropolitan local.

“And, though thought to be “cock rock” compared to revolutionary and reactionary punk, pub rock has been proven to display a strong moral voice in diverse cases.”

Although pub rock has built a reputation for machoism, a brush beyond the surface of the genre reveals an engagement with politics that, while not as prevalent as punk music, still reads as reactionary to the political landscape of Australia and the concerns of its people. Warumpi Band, largely composed of Papunya Aboriginal people, sticks close to the visual and sonic aesthetics of pub rock, with lyrics that traverse considered subjects.[18] “Blackfella/Whitefella” calls listeners to look beyond race (“It doesn’t matter what your colour”) and band together to “stand up and be counted”[19], while more politically explicit track “Jailanguru Pakarnu (Out From Jail)” features lyrics in the Luritja language and shed light on Indigenous incarceration.[20]Midnight Oil are also known for songs that spout beliefs on the social and environmental climate of Australia, even protesting in “hijacking the 2000 Olympic Games Closing Ceremony by performing with the word "Sorry" scrawled across their chest” in a stand against then-Prime Minister Howard’s refusal to apologise for decades of justice against Indigenous Australians.[21] While it is safe to say pub rock has receded from mainstream in current years, certain emerging Australian punk bands keep political issues at the forefront of their messaging. Byron Bay punks Mini Skirt boldly state “I feel no pride in our flag” in B-side “Fun Police” which touches upon a deeply rooted homophobia, sexism and racism embedded in the underbelly of our country's educational and social culture.[22] Pinch Points, Melbourne “smile-punk” band, even go as far to interpolate parliament Question Time audio of previous president Scott Morrison fervently backing the coal mining industry, criticising the environmental impacts, the timely “Black Summer” and “the institutional and government response [...] an absolute shambles”[23] in 2022 track “Virga”.[24] Although punk has a stronger continuing legacy of incorporating left-wing political messaging and social justice sentiments within their music, pub rock is not to be overlooked for its ethical contributions that are retrospectively reviewed and mediated in a reflected sense of Australian living.

When constructing my insights, I sought to pursue an evidence-based argument, drawing on my previous knowledge and catalogue of songs and then sourcing scholarly articles and books that either challenged or affirmed my assumptions. I used two Canvas suggested sources, “Losing the Local…”[25] and “1984 Blackfella/Whitefella, Warumpi Band”[26], using the first to carve out the importance of the “local” pub in Australian music culture and the latter as an example of political stances in the genre. The other three main sources were found through searching techniques on JSTOR and the USYD Library where I went from attempting phrases such as “Australian pub/punk rock” to a more conceptual keyword search, looking for “Australian identities”, “Masculinity in Australian Music” and even specific examples such as “Divinyls” and “Midnight Oil”. Though “So Slide over Here…”[27] took a queer reading on Australian pop, there were also sections that broke down place and masculinity in reflecting Australian life, and “Anzac Memories…”[28]provided the perfect retrospective and historical framework to contrast the growth of the gendered Australian identity. Finally, Henderson’s “Of Witches and Monsters…” explored the gendered nuances in autobiographies by women of Australian rock and offered insights on their mediation which strengthened ideas on their external media identity.[29] No AI was utilised, I either started with a source and looked for music that supported the sentiments or started with song evidence and looked for scholarly affirmation.

A sense of living in Australia is shown to be expansive, nondefinitive and riddled with nuances that go beyond initial identification of representation trends in genres. While white, heterosexual masculine identities feature prominently in both pub and punk rock, female, immigrant and Indigenous perspectives are still to be found yet admittedly stifled. Australian iconic landscapes of bush and beach are highlighted consistently, but metropolitan and pub scenes partially subvert the bush legend. And, though thought to be “cock rock” compared to revolutionary and reactionary punk, pub rock has been proven to display a strong moral voice in diverse cases.[30] Australian rock music, specifically pub rock and punk genres harness identities, places and political discourse that construct their own Australian legend.

[1] Greg Young, “‘So Slide over Here’:The Aesthetics of Masculinity in Late Twentieth-Century Australian Pop Music,” Popular Music 23, no. 2 (2004), 174.

[2] “‘You’re the Voice’: Should Pub Rock and Politics Ever Mix?” Real Sydney News, September 4, 2023, https://www.realsyd.com.au/news/youre-the-voice-should-pub-rock-and-politics-ever-mix.

[3] Alistair Thomson, “Anzac Memories: Putting Popular Memory Theory into Practice in Australia,” Oral History 18, no. 1 (1990), 25.

[4] Choirboys, “Boys Will Be Boys,” by Ian Hulme and Brett Williams, Spotify, track 3 on Big Bad Noise, 1987.

[5] Young, “‘So Slide over Here’,” 174.

[6] Jimmy Barnes, “Working Class Man,” Spotify, track 11 on Hits, 1996.

[7] Margaret Henderson, "Of Witches and Monsters, the Filth and the Fury: Two Australian Women's Post-Punk Autobiographies," Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature 20, no. 1 (2020), 3.

[8] Dan Condon, “The Hard-Ons,” ABC Listen, 20 November 2014, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/the-j-files/the-hard-ons/10274884

[9] Hard-Ons, “Coff’s Harbour Blues,” Spotify, track 13 on Love is a Battlefield of Wounded Hearts, 1989.

[10] Hard-Ons, “Stairway To Punchbowl,” Spotify, track 18 on Dick Cheese, 1988.

[11] Young, “‘So Slide over Here’,” 174.

[12] Australian Crawl. “Daughters of the Northern Coast,” Youtube, accessed 10 September 2024.

[13] AC/DC, “It’s A Long Way To The Top,” Youtube, accessed 10 September 2024.

[14] Shane Homan, "Losing the Local: Sydney and the Oz Rock Tradition,” Popular Music 19, no. 1 (2000), 33.

[15] Amyl and The Sniffers, “Security,” by Amy Taylor and Gus Romer, Spotify, track 4 on Comfort To Me, 2021.

[16] The Chats, “Pub Feed,” by Eamon Sandwith and Joshua Price, track 8 on High Risk Behaviour, 2020.

[17] Cosmic Psychos, “Nice Day to Go to the Pub,” track 1 on Glorius Barsteds, 2011.

[18] Andrew P. Street, “1985 Blackfella/Whitefella, Warumpi Band,” in The Long and Winding Way to the Top. (Australia: Allen & Unwin, 2017), 140.

[19] Warumpi Band, “Blackfella/Whitefella,” by G Djilaynga and N Murray, Spotify, track 2 on Big Name, No Blankets, 1985.

[20] Warumpi Band, “Jailanguru Pakarnu (Out From Jail)” by N Murray and S Butcher, Spotify, track 2 on Go Bush!, 1987.

[21] Dylan Tan, "Mixing Music and Politics: Legendary Australian Musicians and Activists Midnight Oil has Reunited for a World Tour that is Selling Out Across the Globe," The Business Times, 04 Aug 2017, https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/mixing-music-politics/docview/1925864579/se-2.

[22] Mini Skirt, “Fun Police,” track 2 on Hello Possums, 2018.

[23] Taylor Ruckle, “Pinch Points Discuss Balancing Hope and Pessimism on "Process" | Feature Interview,” POST-TRASH, March 14 2022, http://post-trash.com/news/2022/3/13/pinch-points-feature-interview.

[24] Pinch Points, “Virga,” by Adam Smith and Acacia Coates, Spotify, track 6 on Process, 2022.

[25] Homan, "Losing the Local,”.

[26] Street, “1985 Blackfella/Whitefella, Warumpi Band”.

[27] Young, “‘So Slide over Here’”.

[28] Thomson, “Anzac Memories”.

[29] Henderson, "Of Witches and Monsters,”.

[30] Young, “‘So Slide over Here’,” 183.

REFERENCES

AC/DC. “It’s A Long Way To The Top.” Youtube. Accessed 10 September 2024.

Amyl and The Sniffers. “Security,” by Amy Taylor and Gus Romer. Spotify. Track 4 on Comfort To Me, 2021.

Australian Crawl. “Daughters of the Northern Coast.” Youtube. Accessed 10 September 2024.

Barnes, Jimmy. “Working Class Man”. Spotify. Track 11 on Hits, 1996.

Breen, Marcus. “Oz Rock.” Popular Music 7, no. 1 (1988): 98–100. http://www.jstor.org/stable/853079

Choirboys. “Boys Will Be Boys,” by Ian Hulme and Brett Williams. Spotify. Track 3 on Big Bad Noise, 1987.

Condon, Dan. “The Hard-Ons.” ABC Listen, 20 November 2014. https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/the-j-files/the-hard-ons/10274884

Cosmic Psychos. “Nice Day to Go to the Pub.” Track 1 on Glorius Barsteds, 2011.

Hard-Ons. “Coff’s Harbour Blues.” Spotify. Track 13 on Love is a Battlefield of Wounded Hearts, 1989.

Hard-Ons. “Stairway To Punchbowl.” Spotify. Track 18 on Dick Cheese, 1988.

Henderson, Margaret. "Of Witches and Monsters, the Filth and the Fury: Two Australian Women's Post-Punk Autobiographies." Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature 20, no. 1 (2020): 1-14. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/witches-monsters-filth-fury-two-australian-womens/docview/2434744614/se-2.

Homan, Shane. "Losing the Local: Sydney and the Oz Rock Tradition". Popular Music 19, no. 1 (2000): 31-49. https://www.jstor.org/stable/853710.

Mini Skirt. “Fun Police.” Track 2 on Hello Possums, 2018.

Neuenfeldt, Karl, and Kathleen Oien. “‘Our Home, Our Land... Something to Sing about’: An Indigenous Music Recording as Identity Narrative.” Aboriginal History 24 (2000): 27–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24046357.

Pinch Points. “Virga,” by Adam Smith and Acacia Coates. Spotify. Track 6 on Process, 2022.

Ruckle, Taylor. “Pinch Points Discuss Balancing Hope and Pessimism on "Process" | Feature Interview.” POST-TRASH, March 14 2022. http://post-trash.com/news/2022/3/13/pinch-points-feature-interview.

Street, Andrew P. “1985 Blackfella/Whitefella, Warumpi Band.” In The Long and Winding Way to the Top. Australia: Allen & Unwin, 2017.

Tan, Dylan. "Mixing Music and Politics: Legendary Australian Musicians and Activists Midnight Oil has Reunited for a World Tour that is Selling Out Across the Globe." The Business Times, Aug 04, 2017. https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/mixing-music-politics/docview/1925864579/se-2.

The Chats. “Pub Feed,” by Eamon Sandwith and Joshua Price. Track 8 on High Risk Behaviour, 2020.

Thomson, Alistair. “Anzac Memories: Putting Popular Memory Theory into Practice in Australia.” Oral History18, no. 1 (1990): 25–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40179137.

Young, Greg. “‘So Slide over Here’: The Aesthetics of Masculinity in Late Twentieth-Century Australian Pop Music.” Popular Music 23, no. 2 (2004): 173–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3877486.

Warumpi Band. “Blackfella/Whitefella,” by G Djilaynga and N Murray. Spotify. Track 2 on Big Name, No Blankets, 1985.

Warumpi Band. “Jailanguru Pakarnu (Out From Jail)” by N Murray and S Butcher. Spotify. Track 2 on Go Bush!, 1987.

“‘You’re the Voice’: Should Pub Rock and Politics Ever Mix?” Real Sydney News, September 4, 2023. https://www.realsyd.com.au/news/youre-the-voice-should-pub-rock-and-politics-ever-mix.